Daniel C. Wagner

Professor and Chair of Philosophy

Aquinas College, Grand Rapids, MI

Editor, Reality

ABSTRACT: While commentators on APo II.19 generally take note of Aristotle’s break from Platonism in his approach to knowledge genesis, the fact that Aristotle’s approach is yet Platonic goes unnoticed. At the same time, APo II.19 is treated as an incomplete, even embarrassing attempt by Aristotle to answer the question as to the ultimate source of the principles of science. This study exhibits the elegance and completeness of Aristotle’s genetic account of the principles of science at APo II.19 precisely as an exercise of the Platonic method of division, providing an invaluable hermeneutic key for unlocking this extremely difficult and dense text and showing the developmental philosophical continuity that exists between Plato and his student, Aristotle.[1]

1. Introduction

At Posterior Analytics (APo) II.19, Aristotle offers his complete solution to Meno’s eristic argument, which he had breached and partially answered in APo I.1. His solution, which doubles as his answer to the question of how the first principles of a science (ἐπιστήμη/episteme) are known as necessarily true in accord with the canons set down at APo I.2,[2] takes sense-perception (αἴσθησις/aisthesis) as the ultimate source (ἀρχή/arche) commencing a process of induction (ἐπαγωγή/epagoge) leading into the possession of scientific knowledge.[3] Thus, it is generally and rightly seen by commentators as a radical break from a Platonic approach where the first principles of knowledge are said to be possessed innately, needing only to be recollected by the knower.[4] Given the extreme brevity of the text—it is only about two Bekker pages—and the massive scope of the subject Aristotle is treating, most secondary accounts then focus on some aspect or the whole of what is often referred to as the “genetic account” of knowledge.[5] This account, running from 99b34 to 100b17, consists of two stages outlining the genesis of knowledge, beginning with sense-perception and terminating in the apprehension of the first principles of demonstrative science, i.e., primary premises or definitions (τὰ πρῶτα/ta prota), by the faculty of νοῦς (nous) or intellectual-judgment.[6]

What one will not generally find in the growing body of secondary literature on this text is a description of Aristotle’s method as “elegant”, i.e., as a graceful and stylish selection and presentation of the concepts necessary for adequately answering the question of how knowledge of the first principles of science is obtained. Indeed, one will generally find quite the opposite kind of thing being said about the text. In commenting on the two stages of the genetic account, Jonathan Barnes, for example, holds that the first stage is incomplete, and that the second stage is best seen as “correcting and amplifying” the first.[7] Here, then, we must imagine a tired and lazy Aristotle correcting himself on the fly, composing not-so-good notes on a very sophisticated and important epistemological topic. Perhaps the pater peripateticorum exceeded the mean in his walk that day or got his lunch mixed up with that of Milo. D.W. Hamlyn sees the same account as having a “lacuna”,[8] and Greg Bayer has called the whole of APo II.19 “tortuous”.[9] While David Bronstein does refer to APo, generally, as “coherently and elegantly structured,”[10] regarding the genetic account, he notes, “Aristotle omits important stages between the universal and νοῦς, and so there is a gap in his account.”[11]

To call APo II.19 “elegant”, then, would seem a bold claim. To assert that the source of this elegance is Aristotle’s Platonism—given his explicit rejection of the theory of recollection—might seem outlandish, and I hope that it is, at least, provocative. In this study, I will show, first, that Aristotle accepts and uses a Platonic method of division in the two-stage genetic account of APo II.19 and, second, that understanding this shows the elegance and completeness of the text—that in fact, given the task he has set out to accomplish, Aristotle’s two stage genetic account is without any lacunae and complete.

By “Platonic division”, I do not mean, and thus will not treat at all, the dichotomous form of logical division for which Plato is most famous, apparently championed, for example, in the Sophist and Statesman.[12] Aristotle explicitly rejects dichotomous division,[13] as it results in the inclusion of non-essential attributes in the definition, positing instead the need for division by multiple differentia.[14] On the other hand, scholars have generally overlooked the fact that, when it comes to defining animals and their parts—just the kind of defining Aristotle is doing in APo II.19—the Stagirite is, in fact, appropriating and developing a Platonic insight expressed in the Phaedrus, Republic, and also the Sophist, that division arrives at its indivisible terminus when it expresses a δύνᾰμις or capacity by the identification of the functionally-ordered-act (ἔργον) and the affective-object (πάθη) toward which the act is ordered. Here, borrowing a notion from the late philosopher of science, William A. Wallace, I will refer to this approach to division and definition as the “power-object model” of division.[15] In the first part of this study, Plato’s power-object model of definition through division will be presented. In the second portion of this study, it will be shown that Aristotle himself champions the power-object model of definition in his treatment of division in De Partiubs Animalium. Finally, I will show that, in order to explain how the first principles of knowledge are apprehended in APo II.19, Aristotle uses this same power-object model to define the human knowing capacities. Understanding this fact provides an invaluable hermeneutic key for unlocking this extremely difficult and dense text, while showing its elegance and completeness.

2. Platonic Division

A general account of the basic terms and nature of Platonic definition will serve as a helpful and necessary propaedeuticfor understanding Platonic division in the Phaedrus, Sophist, and Republic. This account can be gathered from Plato’s Euthyphro and Meno. In both of these dialogues, Plato’s Socrates explicitly sets down a positive account of what it means to define being or give a λόγος (logos) of οὐσία (ousia).

2.1. Euthyphro

In the Euthyphro, Socrates seeks a definition of the pious and the impious so that he can defend himself against the charge of impiety at his trial. Socrates begins by asking Euthyphro, “what kind (ποῖόν τι) would you say that the pious and the impious are?”[16] The indication, with the interrogative, ποῖόν τι (poion ti), is that a proper account will transcend particular examples or instances and express a common type under which the particulars being defined may be classified. Accordingly, Socrates further asks Euthyphro for some single trait, characteristic, or form (ἰδέα/idea) that is identical to itself throughout the many instances or acts of the pious.[17] Socrates wants an expression of the common or universal “form (τὸ εἶδος/to eidos) by which all things said to be pious are pious.”[18]

The term εἶδος (eidos) may seem to tie Plato’s account of definition inextricably to the famous Platonic theory of the separated forms/ideas (τὰ εἴδη).[19] We know that Aristotle rejected this theory in principle and in its connection to the theory of ἀνάμνησις (anamnesis) or recollection.[20] It would be untenable, then, to claim that he uses such a Platonic theory of definition in APo II.19. Some remarks are warranted, thus, regarding the etymology and history of the term, in order to extricate the theory of Platonic definition and division that Aristotle accepts and utilizes in APo II.19 from the theory of Ideas. ἰδέα (idea) and εἶδος (eidos) are both derived from the verb εἴδω (eido), meaning ‘see’.[21] Literally, then, the terms signify the ‘look’ of something seen,[22] and in their original sense they applied to the ‘figure’ or ‘physique’, particularly of the human body as a whole or in some part, in accord with which beauty or ugliness could be predicated.[23] Plato inherited the technical meaning of these terms as signifying a trait universally belonging to a set of particulars from Socrates, who took it, in turn, from the Pre-Socratic accounts of written composition, medicine, philosophy, and, ultimately, Pythagorean mathematics.[24] The rhetorician, Isocrates, used the terms synonymously to mean the form or composition of accounts (σκῆμα λόγου) or of speech (σκῆμα λεξεως) or of thought (σκῆμα διανοίας).[25] Democritus, having been exposed to Pythagorean mathematics by the Eleatic, Leucippus, used “form” (ἰδέα) to classify his atoms in purely geometrical terms.[26] The use of the term as a full-blown tool for classification, then, becomes fully manifest in the medical corpus of Hippocrates,[27] where, for example, εἶδος is used to signify a generic bodily constitution of a certain population of women, which is linked with their deaths. The women who died in a particular case were all of a certain bodily form or constitution (i.e., εἶδος).[28] The meaning of the term, then, as Plato has inherited it, need not necessitate the added thesis that the εἰδή are separately existing individuals. As a consequence, we are free to posit that Aristotle accepts and develops the Platonic account of definition centering on the expression of εἶδος, without falling afoul of the charge that this would entail the further and false claim that Aristotle accepts and utilizes the Platonic theory of separate ideas.

To return to the Euthyphro, the form as a universal meaning that makes pious acts to be pious can be used by Socrates as a “model” (παράδειγμα/paradeigma)[29] for discerning any particular pious act as such. Moreover, this model, would express the οὐσία (ousia)[30] or the being of the pious—what “belongs to it properly”—as opposed to a merely affective attribute, like being ‘loved’,[31] which happens to it from outside itself. The form as a model, it is clear, will not only cause us to know the pious when we “see” it in particular instances as the pious, it will also be the cause of the particular instances being pious—it will be what belongs to them in their very being as pious acts or things. This kind of account would constitute an answer, thus, to the generic question that Socrates is probably most famous for asking: τί ἐστι or “what it is”.[32] Finally, anticipating Aristotle’s Topics and Categories at the culmination of the dialogue, Socrates leads the wearied Euthyphro to define the pious in terms of a larger whole or genus and the characteristic that sets it apart, or the specific difference: “…the part of the just,” he says, “that is both pious and holy is that concerned with service to the gods…”[33]

2.2. Meno

In the Meno, Socrates presses the dialogues namesake for an account of virtue (ἀρετή/arete), so they might answer as to whether or not it is teachable,[34] presenting an approach to definition paralleling the Euthyphro with a few important additions. As in the Euthyphro, Socrates wants a definition in answer to the question τί ἐστι, or ‘what is it?’[35] Again, the definition (τί ἐστι) will capture the being (οὐσία/ousia)[36] of the definiendum, and this will also be a single form (εἶδος/eidos), common to the various types of what is being defined.[37] There is then, again, at least prescience of the relation of genus and species, as Socrates corrects Meno for failing to see that justice is not the whole of virtue itself, but rather one virtue, just as ‘roundness’ is not ‘figure’ itself, but rather a particular species of ‘figure’.[38] Adding to the account, Socrates offers an example of a definition (τί ἐστι/ti esti) of figure, defining it as “that alone among beings which happens always to be belonging with color.”[39] What is learned here is that, while a complete definition would locate the definiendum specifically in a larger whole or genus, an adequate one will at least be expressive of some trait or feature that necessarily belongs to or with the definiendum. The necessity of the relation, in this case, is derived from the fact that no concept of a seeable figure can be formed without color: if one cannot see distinction through color, one cannot see figure.[40] At the highpoint of the dialogue, Socrates then produces a definition (τί ἐστι/ti esti), following this model.[41] Arguing ἐξ ὑποθέσεως (ex hupotheseos),[42] Socrates is able to show that virtue is a form of or is always necessarily with practical wisdom (φρόνησις).[43]

From the Euthyphro and the Meno it is gathered, then, that a definition must express what something is (τί ἐστι/ti esti) in terms of its form (εἶδος/eidos or ἰδέα/idea) and being in the sense of property or what properly belongs (οὐσία/ousia). This form is expressive of a kind (ποῖόν τι/poion ti), and capturing it in terms of generic and specific differences, it is used as a universal[44] model (παράδειγμα/paradeigma) in identifying particular instances. Thus, Socrates asks Meno to define virtue κατὰ ὅλου (kata holou)or according to the whole at 77c. Finally, an important method for defining involves showing that something necessarily belongs to or goes along with (ἐπί) something else, ideally in terms of a genus or species. In these accounts of defining, however, a question remains as to how the philosopher is to know when the process of defining has reached its terminus. Is attaching a universal meaning to a subject of inquiry sufficient for knowing what it is in its totality? When do we know that we have captured the proper being, form, or nature of what is being defined? These questions are answered in the Phaedrus, where the topic of answering τί ἐστι (ti esti) by the method of division is given its most fundamental treatment by Plato.

2.3. Phaedrus

The Phaedrus is a dialogue on the topic of love (ἔρος/eros) and the art of rational discourse, rhetoric, or dialectic.[45] Here, a successful discourse is distinguished from a bad one precisely in that it begins with a general definition as its principle, achieved by gathering or collecting together what is common to a set of particulars, and then, by division, determines the appropriate sub-forms or species. Socrates explains that the definition is achieved through two stages. The first is,

To bring together (ἄγειν) that being seen (συνορῶντα) variously (πολλαχῇ) in the scattered particulars (διεσπαρμένα) into one form (Εἰς μίαν ἰδέαν), in order that each particular, being divided (ὁριζόμενος), may be made manifest, concerning which one now wishes to instruct.[46]

Once one has gathered together a common whole divided from others in this manner, preparing the way for further division, one must divide out its sub-forms. Drawing an analogy between division and the art of the meat-butcher, Socrates sets down the second stage necessary for being a good dialectician:

The ability to cut through again the forms at the joints which have come to be by nature, and to attempt to not break even one part—being abusive in the manner of a bad butcher.[47]

Plato’s explanation as to how the forms and the their joints are recognized, begins with the point that, as with any τεχνή (techne), the τεχνή (techne) of dialectic requires discussion about nature (πέρι φύσεως/peri phuseos).[48] The τεχνή (techne) of dialectic is then compared to that of medicine, as formulated by Hippocrates: “In both cases, one must define nature (φύσιν/phusin), the body in the case of the one and the soul in the case of the other.”[49] Socrates then explains how it is that, through reason, we come to know the nature or being:

That is well then, and consider at length what both Hippocrates and true reason (ὁ ἀληθὴς λόγος) say concerning nature (περὶ φύσεως). For, concerning the nature of anything whatsoever, must we not reason (διανοεῖσθαι) in this manner: first, concerning that which we ourselves wish to be technically knowledgeable of and to be able to make another as such, [we must answer as to] whether it is simple or multiform (ἁπλοῦν ἢ πολυειδές), and then, if it is simple, examine its capacity (δύναμιν), what it is naturally productive of in relation to the act it holds, or what it is in relation to the affection by that which acts upon it, and if it has many forms, these being numbered, as we said regarding one, to see these and say of each of them, what is the act (τί ποιεῖν) for which it has naturally come to be, or what is the affection (τί παθεῖν) for which it is naturally and what acts upon it?[50]

Knowledge of nature is obtained by the division of an object until it is grasped as simple or where its different parts are grasped as simples, meaning the dividing process can no longer continue. Indivisibility is discerned by grasping the act a thing possesses in relation to its production or ‘the agent on account of which it is acted upon.’ Thus, to grasp the nature of a thing, it turns out, just is to be able to define a thing in terms of its operation and the object of its operation. The dividing process reaches a terminus when the proper act and/or receptive-capacity of the thing being defined has been apprehended. A capacity or power is apprehended in relation to that which its act is ordered and which affects it as a power. This “power-object” model of definition is extremely significant to the extent that it allows us to explain why certain features of a thing belong to it necessarily. Such features can be called essential. They are not essential merely because they are ‘common’ or ‘universal’ to a set of particulars. Rather, they are essential because they mark out ontologically the capacities of acting and being acted upon unique to an individual and common to individuals belonging to the same class.[51] Following this power-object model, Socrates prefaced his second and pious speech on love in the Phaedrus with the following remark, which connects his account of division explicitly to the functional-act (ἔργον/ergon) of the definiendum:[52]

We must first, therefore, understand the truth concerning the nature of the soul, both that of the divine and the human kind, [by] examining its receptive capacities (πάθη) along with its functionally ordered acts (ἔργα). This [truth] is the principle (ἀρχὴ) of demonstration (ἀποδείξεως).[53]

The act and the receptive capacity are unified in the being which is to be defined in relation to the object: the being acts for the object which it must also be capable of being affected by precisely in order to act for it. This point is evidenced in the Sophist. Recall that, in both the Meno and the Euthyphro, Socrates explained that a definition must express the being (οὐσία/ousia) of the definiendum. One can ask the question: ‘what is the being?’ One can say that it is the one form that makes something to be what it is and to be known as what it is, but the question remains as to how we know when this one form has been apprehended. In the Sophist, this question is asked and answered by the dialogue’s main speaker (an Eleatic stranger):

I speak of anything whatsoever possessing a capacity (δύναμιν),[54] either in respect of a natural capacity of acting (τὸ ποιεῖν) on any other thing or in respect of being acted upon (τὸ παθεῖν) even in the smallest manner by slightest thing—all this really is. For I am setting down a definition (ὅρον): the things that are (τὰ ὄντα) are nothing except some kind of capacity or power (δύναμις).[55]

Socrates accomplishes the task of defining in this manner, in the Phaedrus, through the image of the soul as a charioteer drawn by two winged horses. This is an image he knows Phaedrus can comprehend, which nonetheless implicitly contains the basic divisions of the soul for which Plato is famous:[56] the non-rational appetites, the irascible-emotional (spirited), and reason. One of the horses is good, representing the love of honor in accord with self-control and moderation, a friend of true beliefs which abides by the command of reason. The other, of ill breed, represents an unfettered and licentious desire for physical pleasure (sexual pleasure, especially).[57] The charioteer represents the rational part of the soul, which is meant to rule the horses, as their driver. Knowing the nature of Phaedrus’ soul and what is good for him, Socrates is able to persuade him that love in its true meaning is a divine madness, or an enthusiasm (ἐνθουσιάζων/enthusiadzon), ordered ultimately to the perfection of the human being.[58] This perfection is the apprehension of knowledge in the Forms.[59] The natural power/capacity of the soul is reason. Its act is understanding in the Forms, and the Forms are the objects capable of affecting it.

2.4. Republic

In the Republic, the Platonic approach to division is utilized by Socrates to obtain a definition of the soul and, in turn, show the good of the human in order to refute Thrasymachus’ claim that injustice is always more beneficial than justice to the one who can avoid being caught.[60] The interest, here, is the definition of the human soul (ψυχή/psuche) through the method of division set down in the Phaedrus. A preliminary account is first given at the end of Book I, where Socrates defines the soul through its functional-acts (τά ἔργα/ta erga) of “taking care of things, ruling, and deliberating.” [61] In Book IV, having provided the larger and more easily grasped account (λόγος/logos)[62] of justice in the good city by dividing it into the three classes of the wise rulers, warriors, and laborer producers of material goods, along with the corresponding virtues of wisdom, courage, and moderation (428a-433b), Socrates provides a more sophisticated division (ὁρίζω/horidzo)[63] of the soul. Utilizing, again, the functional approach, along with the principle that the same thing cannot be its opposite, he divides the human soul into three forms/aspects (εἰδή/eide): (1) the reasoning (λογιστικός/logistikos), (2) the non-reasoning (ἀλόγιστος/alogistos) appetitive (ἐπιθυμητικός/epithumetikos), and (3) the irascible-emotional (‘spirited’) part capable of anger and courage (θυμός/thumos).[64] This account does allow Socrates, once again, to show that injustice is in principle incompatible with the good of the soul, since it would entail a disordered relation of the forms and their lack of fulfilment, which is akin to a physical sickness.[65] However, as we have seen, the canon of the Phaedrus held that a proper division is accomplished by expression of the power-object relation, so that there is yet a need to walk the longer and more complete road.[66]

The move to give, again, a more precise definition of the reasoning aspect of the soul begins in Book V, after Socrates has expressed that the good city can only come about where philosophers rule (473c-e). He must define the philosopher in terms of his desire or love (ἔρος/eros),[67] i.e., the truth, and the faculty by which it is grasped. Ultimately, he must give an account of how the philosophers’ capacity allows them to grasp the form of Justice as a model (παραδειγμα/paradeigma)[68] in order to rule the city properly and perfect themselves. The final refinement of this account comes in the divided line passage of Book VII (509d-511e). Here, the focus will be on Book V, where Plato explicitly develops the division doctrine of the Phaedrus and uses it to define knowledge.

Socrates begins by distinguishing between the Forms and the many perceptible things (bodies) that participate in them, and he equates the Forms with the true (476a). He can then distinguish the philosopher as a knower from those who are ignorant or merely have opinion by using the method of division through δύνᾰμις (dunamis), or the power-object model. Socrates is explicit about his use of this methodology, which constitutes the “longer more complete road” to a definition of the soul:

We will suppose that capacities (δυνάμεις) are the definitive what kind (γένος τι) of beings (τῶν ὄντων), which enable us to be able to do [the] things [we do] and all the other things whatsoever that we might be able to do.[69]

Socrates then explains how a capacity is defined with respect to its proper object, in line with the Phaedrus:

In the case of a capacity (δυνάμεως), I only look to both that for which it is [i.e., its object] and to that which is its perfected work or function (ὃ ἀπεργάζεται), and I would indicate each possessed capacity (δύναμιν) by these. I would call what is ordered toward one thing itself and is functionally-perfected (ἀπεργαζομένην) in acting for that thing [precisely] the same thing, and that which is ordered toward another thing and functionally-perfected in acting for it something different.[70]

This method of division is then used to define the philosopher through the capacity of knowledge. Knowledge (ἐπιστήμη/episteme)[71] is defined under the genus (γένος/genos) of capacity (δύνᾰμις/dunamis)—indeed, it is the “most powerful of all capacities.”[72] It is ordered toward what is (τὸ ὂν/to on) as its proper object,[73] while ignorance (not really a faculty at all, but a privation) is ordered toward what is not.[74] The capacity of opinion is then related to the many particulars that are through participation in what is, but also are not as they are mutable.[75] The philosopher—the one who loves wisdom—is defined then through his capacity: it is being ordered to the objects of knowledge (beings), which are for it.[76] The indivisible acting and receptive capacity has been grasped in accord with the dividing canon set down in the Phaedrus, and restated here in the Republic. The nature (φύσις/phusis) of the philosopher is to love the true which is being and the form, for which his intellect is fitted.[77] Here is a diagram showing Plato’s use of the power-object model to define the philosopher:

Plato’s Power-Object Model of Division

| Capacity (δύναμις) | Affective-Object (πάθη) & Functional-Perfection (τὸ ἀπεργαζόμενον) | |

| Knowledge (ἐπιστήμη) | → | Being/What is (τό ὄν) as nature (φύσις) and form (εἶδος) and the power-object relation (δύναμις) |

| Belief (δόξα) | → | What is and is not (εἶναι και μὴ εἶναι) |

| Ignorance (ἄγνοια) | → | Not Being/What is not (μή τό ὄν) |

3. APo II.19 & Division in De Partibus Animalium

In order to see that Aristotle accepts and develops Plato’s power-object model of division, and then that he employs the model in APo II.19, we begin with the Stagirite’s account of defining being or substance (οὐσία/ousia) in itself[78] at APo II.13-14. Aristotle commences APo II.13 by expressing his intention to “set down the manner in which we must seek those things predicated in the definition (ἐν τῷ τί ἐστι/en to ti esti).”[79] He summarizes the method of division as a process starting with generic attributes and then working by further division down to the particular species.[80] Here, Aristotle gives a general and abstract treatment of division, as it is to be utilized in all the sciences, dividing it into three stages:[81] (1) the collection of attributes connected in some way to a subject; (2) the ordering of these attributes from the highest genera to the lowest species; and (3) showing that the essential attributes belong to the subject in itself with necessity. Aristotle does not give a precise account of how the subject-domains of animals, under the genus of beings of nature, are to be defined in this text.[82] This account is given at the outset of the De Partibus Animalium.[83] Here, it is clear that Aristotle accepts the method of division by δύνᾰμις (dunamis) or the power-object model, from his teacher of twenty years, Plato.

In order to explain the division of animals and their parts, Aristotle, like Plato, appeals to the concepts of functional-act (ἔργον/ergon) and capacity or power (δύνᾰμις/dunamis). However, and adding greater intelligibility to these concepts, Aristotle appeals to the rich teleological character of nature that he set down in the Physics—incipient in Plato, as we have seen, but undeveloped. Criticizing Empedocles at length for not grasping that the process of generation itself is determined by the end and the form, Aristotle notes that he failed both to recognize that a seed is already present with the capacity or power (δύνᾰμις/dunamis) to achieve the end, and that an agent of the same kind produced the seed in the first place.[84] According to Aristotle, further, the teleological power of natural beings is displayed in their functional-acts:

For not what is by chance, but that for the sake of which (ἕνεκά) exists most of all in the functional-acts (ἐν τοῖς ἔργοις) of nature; and where [animals] have been constituted or come to be for the sake of the end, this has taken the place of the good.[85]

Aristotle had shown in Physics I.7, that every natural being is a complex of matter and form. The motion of natural beings can only be explained in so far as they are materially capable (qua subjects) of becoming a positively possessed form or disposition, which is not at first actually present. The per se movement of natural beings, moreover, as Aristotle sets down and develops in Physics II.1, 3, 4-6 and 8-9, is toward the form or expressed essence, which is thus taken by Aristotle as the end, and the final cause by which natural motion is explained.[86] In PA, Aristotle then directly connects this teleological conception of natural causal explanation to division through an analysis of the morphological forms correlated with the functional-activities of the animals and their parts being defined. He works elegantly from our better-known understanding of the parts of things, which clearly possess a functional-act toward an end as instruments or organs, to the functional-act of the whole organism to which the parts belong:

Since every organ is for the sake of something, and each of the parts of the body are for the sake of something, and the that for the sake of which is a distinct activity (πρᾶξίς), it is also clear that the whole body has been constituted through various parts for the sake of some activity. For the sawing has not come to be for the sake of the saw, but the saw is for the sake of the sawing; for sawing is a certain use. Therefore, also, the body is for the sake of the soul in this manner, the parts are [for the sake] of the functional-acts (τῶν ἔργων) in relation to which each has come to be by nature (πέφυκεν). Therefore, one must first state the activities—those common to all, those common according to genus, and then those according to species.[87]

In dividing, thus, Aristotle holds that we correlate observed life activities with the functional-acts of the organic parts or forms of the animals, or the whole beings (οὐσίαι/ousiai) ordered toward the activities as the ends or that for the sake of which.[88] It is not just that the animal possesses an essence or form ordered to a determinate end, i.e., the activities unique to its kind, but there is a thorough teleological ordering of each of its organs toward the life activity of the whole organism.[89] As Lennox has shown, the organic capacities of the animal are “coordinated” in their order toward the specific normative life activity of the animal.[90] How, then, do we move from grasping the activity of an animal through observation to understanding the kind of an animal in and through its parts? Aristotle explains, following Plato, that what is is to be defined with respect to its kind or genus (τῷ γένει) in terms of its capacity or power (δύνᾰμις), and the actual object to which it is ordered in its activities:

What is is acted upon in [its] capacity by what is actual, so that both the former one and the latter one are the same with respect to genus.[91]

Aristotle provides a fine example in PA IV, dividing long-legged birds, and giving the causal explanation of the morphological feature, noting that the organs of animals are for the sake of their end-directed functional-acts, and not vice versa:

Some of the birds are long-legged. The cause of this is that their mode of life is marsh-dwelling. For nature produces the organs for the sake of the functional-act (τὸ ἔργον), but the functional-act is not for the sake of the organs. Thus, because they are not swimmers, they are not web-footed, and it is on account of their mode of living, in residing [in the marsh], that they are long-legged and long-toed, and many of them possess many joints in their toes.[92]

As with Plato, then, Aristotle understands that we obtain knowledge of a natural, animal kind by grasping a capacity as ordered to the object it acts for the sake of and which (in many cases) affects it. Here, having located the being in the genera of animal, bird, then aquatic type bird he identifies proper differentia in the morpholical features of long-legged, long-toed, with many joints as dividing the marsh dwelling bird from its cousins with webbed feet and short legs. The process of division of the animal is also a proper definition,[93] as it provides the teleological causal explanation of the relevant morphological features: the reason for the fact of these morphological features is the mode of life of this being—its functional-act (ἔργον/ergon) and normative life behavior (πρᾶξις/praxis)—flourishing in marsh lands as it does. This interpretation of the Stagirite’s conception of the power-object model of division and causal explanation is also well supported by the following texts from Politics and Meteorology:

And everything is defined by its functional-act (τῷ ἔργῳ) and capacity (τῇ δυνάμει).[94]

And again,

Everything is defined by its functional-act (τῷ ἔργῳ); for the objects (δυνάμενα) of the capacities produce their functional-acts which is what each thing truly is; for example, if it were the eye, it would be the act of seeing, and when there is no capacity the thing is only called what it is equivocally, as when the body dies or in the case of the stone body.[95]

Accordingly, this method is clearly utilized by Aristotle in his work in the life sciences, especially De Anima, and in the Ethics and Politics.[96] Let us turn to show Aristotle’s use of this developed Platonic methodology in APo II.19.

4. The Power-Object Model of Division & APo II.19: Stage 1 of the Genetic Account

Aristotle’s express concern at APo II.19 is to answer as to how the first principles (ἀρχαί/archai) of science come to be known, and what the knowing state (γνωρίζουσα ἕξις/gnoridzousa hexis) is in which they are grasped.[97] The answer to these questions, simultaneously, constitutes his own solution to Meno’s eristic argument. Meno expresses a dilemma, formed in the disjunction that, either we know without qualification, or we do not know without qualification.[98] It is then concluded that coming to know is impossible. If we already know, of course, we cannot come to know. On the other hand, if we have absolutely no knowledge, then there is no point of departure or source for coming to know. Thus, in the face of the experiential fact that learning does seem to happen, the dilemma requires an answer to the question: “what is the source of knowledge?”[99] The question is even more urgent and pointed in APo, because Aristotle has made the claims here that the first principles of a science, which are the definitions and premises that allow for scientific demonstration, (i) must necessarily be true, and (ii) cannot themselves be scientifically demonstrated (through middle-termed reasoning).[100] Thus, the question that must be answered by Aristotle in APo II.19 is: how is it that the first principles of a science are grasped as necessarily true, and not by middle-termed demonstrative syllogisms?

Aristotle begins by rejecting a Platonic approach at the outset, which holds that the first principles are innately possessed.[101] Using the power-object model, he then answers that he ultimate source of knowledge, rather, is a “natural or inborn capacity (δύναμις/dunamis) of discernment (κρῐτῐκός/kritikos), which, is called sense-perception (αἴσθησις/aisthesis),” and which all animals possess.[102] Along with sense-perception, some animals possess also the capacity of memory, i.e., the retention (μονὴ/mone) of the perceived (τοῦ αἰσθήματος/tou aisthesmatos) in the soul.[103] After sense-perception and memory, Aristotle notes that a further “distinction arises that for some [animals], out of such remaining [perceptions as memories], there comes to be reasoning or a reasoned-account (λόγον/logon).”[104] In order to answer as to the ultimate source of knowledge, Aristotle has thus divided out kinds of animals by appeal to the concept of δύνᾰμις (dunamis), power or capacity. In general, animals have the sense-perceptive capacity. Then, there are others that also have memory. Finally, there are human beings which are divided further in the genus by the capacity of λόγος (logos).[105] Already, then, the developed use of the Platonic, power-object model of division is apparent.

At this point, Aristotle pauses to summarize his account, and he adds to it the fact that through these capacities the knowing state of experience (ἐμπειρία/empeiria) is produced:

From sense-perception, then, comes to be memory, precisely as was said, and from many memories of the same thing comes to be experience (ἐμπειρία); for the many memories (with respect to number) are one experience.[106]

In the rational animal, then, which possesses these capacities, they are genetically stacked upon each other so that the higher order capacity presupposes the lower order, and they are productive of the knowing state of experience (ἐμπειρία/empeiria). Immediately, Aristotle conveys something of what experience constitutes, equating it with the apprehension of a universal,[107] and he asserts that it is the source (ἀρχή/arche) of knowledge both in the technical arts and in science:

And from experience or every universal being established in the soul—the one in relation to the many, which one would be the same in all the many particulars—[is] the principle of art and science: if it concerns production, art, if it concerns being, science.[108]

At this point, Aristotle can answer as to how the first principles come to be known in the sense of what their foundational source or ἀρχή (arche) is. What he says is that the pre-existing knowledge states requisite for all reasoning have their principle or source in the δύνᾰμις (dunamis) or capacity of sense-perception:

Neither, then, are these states [of knowledge] pre-existent in definite from, nor do they come to be from other better-known states [of knowledge], but [they are] from sense-perception…[109]

We are to understand, then, that the state of human knowledge called experience is the source of scientific understanding and it is generated through sense-perception, memory, and reason. The first stage of Aristotle’s genetic account of knowledge is complete. The precise nature of these knowledge states, however, is yet to be fully disclosed in accord with the Platonic and Aristotelian conception of power-object model division. In order to begin to shed light on how it is that sense-perception is the source of knowledge, Aristotle first poses an analogy. Knowledge comes to be from sense-perception, he says,

as it is like in a battle when a turning about of the enemy has come to be by one standing and another making a stand, and then another, until it [i.e., the route] has come to be by the principle; and the soul belongs to such a type of being as to be able (δύνασθαι) to be affected (πάσχειν) in this manner.[110]

In a battle, where one side that is supposedly in duress turns the tide and defeats its enemy, the first soldier to turn and make a stand, ending the retreat, provides a principle for the whole victory. All that follows in the end, namely the stacking of the other soldiers in the formation of a line and the victory, is in a way present in the first soldier who is recognized as the first and ultimate source of the victory. Analogously, Aristotle wants to hold that the human soul, starting with the capacity of sense-perception, is capable of forming experiential and scientific knowledge states. Something is present in sense-perception, thus, which anticipates and leads to these knowledge states, as the first soldier was present and led to the victory. We are left, ourselves, in anticipation, as to what this something is. However, and most important to the end of this study, Aristotle has again, in the final clause of this statement, explicitly appealed to the power-object model of defining, by noting that the soul belongs to the class of beings capable of being affected in such a manner as to come to know.

5. The Power-Object Model of Division & APo II.19: Stage 2 of the Genetic Account

Immediately before beginning the second stage of his genetic account, Aristotle indicates that the account he has given to this point must be developed as it has been stated οὐ σαφῶς (ou saphos)—i.e., not clearly or without distinction.[111] It must be emphasized that Aristotle is not saying that the initial account is in error, or that it is incomplete. Rather, this statement fits his general methodological principle that we move from what is better-known to us, to what is better-known to nature through division.[112] Prior, general states of apprehension are not ‘false’ or ‘wrong’. They simply need to be divided for higher levels of precision. In stage 1 of the genetic account, Aristotle has set out the better-known capacities by which knowing is possible, first grasped and apparent as functionally directed activities (ἔργα/erga) and he has explained that the state of experience as constituted by universal judgement is the source of technical and scientific knowledge. As we learned from Plato and the power-object model of division, to attain full precision regarding what we are dividing or defining, the capacities and corresponding states must be distinguished in terms of their proper objects, i.e., what they act for and what affects them.

Aristotle begins to achieve the needed precision by connecting sense-perception (αἴσθησις/aisthesis) to the particular, which is also the latent source of proper knowledge in the apprehension of an unqualified universal. Sense-perception, he says, is of the particular individuals (καθ’ ἕκαστον/kath hekason), but as he has already indicated that it is a kind of discernment (κρῐτῐκός/kritikos), he notes also that it must entail what is universal (τὸ κατόλου/to katolou):

One of the undifferentiated things having made a stand, the first universal [is constituted] in the soul (for though one perceives the particular (τὸ καθ’ ἕκαστον), sense-perception [judgment] is of or by the universal (τοῦ καθόλου), for example, of ‘human,’ and not Kallias the human)…[113]

In sense-perception then, an individual is perceived as the object of perception per se, but there is also judgment that the individual belongs to a kind which is universal and this belongs to the capacity of reason per se. I discern, to follow Aristotle’s example, that this particular individual, namely, Kallias, is a ‘human’. I perceive this particular being as a certain kind (human) or existing with a certain attribute. Such a perception would allow me to say, “that is a human”. Perceiving other beings like him, say horses, fish, frogs, chickens, etc., I come to form more and more generic concepts until my intellect hits the highest genera, which are the categories. So, Aristotle says,

[…] and by these [initially undifferentiated things] again making a stand [the universal is constituted], up to the point that the indivisible universal makes a stand; for example such and such an animal, until ‘animal,’ and similarly by this [all the way to the highest universals].[114]

By perceiving particular beings in the world, thus, human knowledge rises from the lowest universals, intended as of the particulars, up to the highest “indivisible” universals, genera, or the categories.[115]

Aristotle has used the Platonic, power-object model of definition, dividing the sense-perceptive capacity from the capacity of reason by expressing the proper object of each: the proper object of the sense-perceptive capacity is the particular (what is sensed and remembered) while the proper object of reason is the universal. In acts of sense-perceptive judgment, as we have seen, the two powers act together so that human beings can classify the particulars under universal genera, species, and differentia.

To return to Aristotle’s analogy of the route in battle, it is clear that the analogous principle in knowing is the sense-perceptive universal. As ‘undifferentiated’, it is in potency to being divided into its primary aspects. Scientific knowledge as the end, is thus in a way present in the sense-perceptive universal already, just as victory was present, in a way, in the first soldier to turn, stop, and start the line. Once I have formed sense-perceptive universals, I may then use the capacity of reason (λόγος/logos) to arrive at a proper understanding of the unqualified universals, which are the first principles of a given science. That Aristotle holds this view of the progression of human knowledge is most clear from his comments on methodology at Physics I.1:

What is first manifest and clear to us, rather, are things taken together without distinction (τὰ συγκεχυμένα). Later, the elements and principles come to be known by the division of these. Therefore, it is necessary to advance from the universals (ἐκ τῶν καθόλου) to the particulars (ἐπὶ τὰ καθ’ ἕκαστα). For the whole (τὸ ὅλον) according to sense-perception (κατὰ τὴν αἴσθησιν) is better-known (γνωριμώτερον), and the universal is a certain whole—for the universal embraces many things as its parts.[116]

Aristotle concludes APo II.19 by setting down that the state of knowledge in which the first principles of a science, i.e., τά πρωτα (ta prota), are apprehended, and which follows from sense-perception of the particular, memory, experience, and a reason, is νοῦς (nous), intellectual-judgment, wherein the reasoning capacity has apprehended its proper object, the unqualified universal.[117]

6. Conclusion

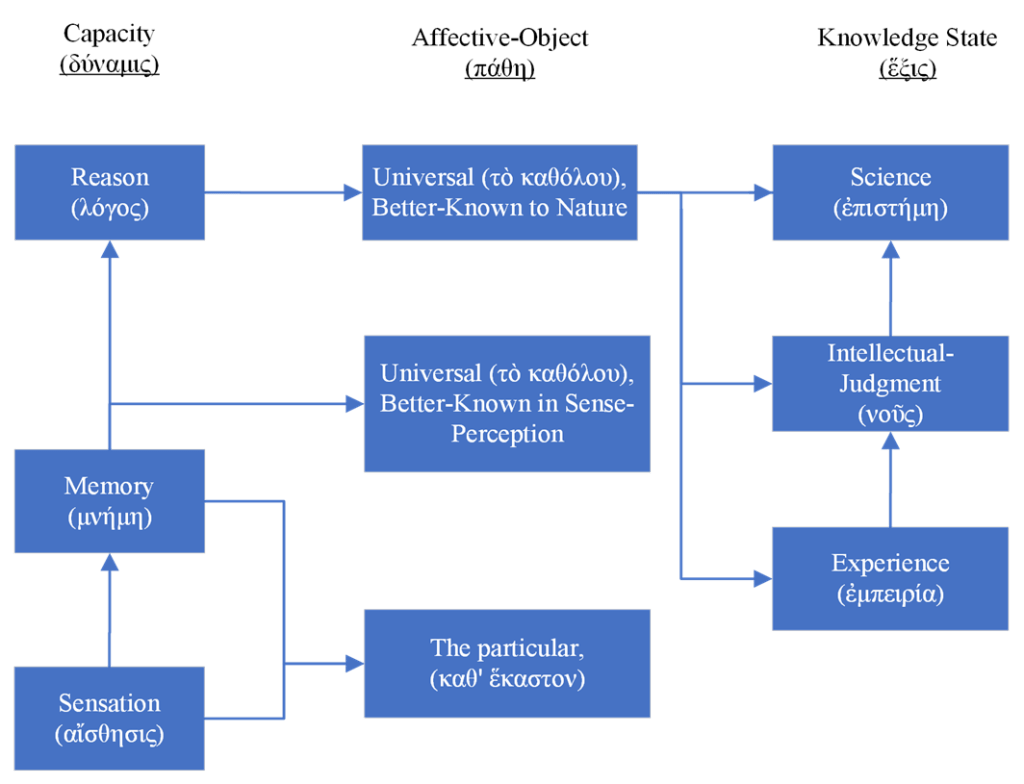

In answer to the questions he set out at the beginning of the text, Aristotle clearly expresses that the ultimate source of knowledge is the capacity of sense-perception, and the knowing state that grasps the first principles is intellectual-judgment. In order to produce these answers in accord with his own canons on knowledge of primary principles, definitions, or premises, Aristotle employs the method of division by δύναμις (dunamis) first developed by Plato. In the first stage of the genetic account, Aristotle sets down the capacities adequate for explaining how knowledge of first principles is obtained: sense-perception, memory, and reason. However, and as we saw Aristotle explicitly indicate before moving into the second stage, these capacities and the knowledge states which they produce are initially stated without distinction(οὐ σαφῶς) in stage 1.[118] The reason for this, is that he has not yet divided them in terms of their proper objects. This, precisely, is what he accomplishes in the second stage of his approach, where, through analysis, he correlates the capacities and the states they produce with their proper objects, namely, the particular and the universal. The following schematic diagram relates each of the capacities set down to their objects along with the knowledge states that they produce:

The Power-Object Model of Division in APo II.19[119]

By understanding Aristotle’s Platonic method of division as evidenced in PA and here in APo, II.19, the elegance and completeness of his approach in the two-stage genetic account of knowledge has been disclosed. Aristotle has carefully and gracefully selected precisely the capacities adequate for explaining how knowledge of the first principles of a science come to be, and he has distinguished these capacities in terms of their proper objects. Understanding, now, that the two-stage genetic account is the process of moving from a better-known to us understanding of the powers that lead to knowledge to a better-known to nature understanding of these same powers by correlation with their proper objects, it is manifest that the text of APo II.19 is elegantly composed, having no gaps or lacunae.

References Historically Layered

ARISTOTLE (384—322bc).

c.353–47bc. Φυσικὴ ἀκρόασις (Physics) translations by the author but refer to the Loeb edition, English translation by Philip H. Wicksteed and Francis M. Cornford (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Vol. I. 1957, Vol. II. 1934).

c.348-47bc. The Works of Aristotle, edited by J.A. Smith and W.D. Ross, English translation by G.R.G. Mure (Clarendon Press, Vol. I. 1928).

c.348-47bc. Ἀναλυτικὰ Ὕστερα (Posterior Analytics), English translation by Hugh Tredennick and E. S. Forster (Harvard University Press, 1960).

c.348-47bc. Ἀναλυτικὰ Ὕστερα (Posterior Analytics) English translation by Hippocrates G. Apostle, (Grinnell, IA: The Peripatetic Press, 1981).

c.348-47bc. Ἀναλυτικὰ Ὕστερα (Posterior Analytics) English translation by Jonathan Barnes, 2nd edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).

c.348-30bc. Μετά τα Φυσικά in the Basic Works of Aristotle prepared by Richard McKeon, in the English translation by W.D. Ross, Metaphysics (New York: Random House, 1941).

c.339bc. Μετεωρολογικά (Meteorology).

c.331bc. Περὶ Ψυχῆς (De anima).

c.330bc. Περὶ ζῴων Μορίων (Parts of Animals) with translation by the author but reference to that by Lennox, Aristotle on the Parts of Animals: I-IV (2001).

c.330bc. Τῶν περὶ τὰ ζῷα ἱστοριῶν (History of Animals).

c.328bc. Πολιτικά (Politics).

BALME, David (8 September 1912—1989 February 23).

1987. “Aristotle’s use of division and differentia” in Philosophical Issues and Aristotle’s Biology (ed. Allan Gotthelf and James G. Lennox) (New York: Cambridge University Press).

BAYER, Greg.

1997. “Coming to Know Principles in Posterior Analytics II 19” in Apeiron 30: 109-42.

BURGER, Ronna (5 December 1947—).

2008. Aristotle’s Dialogue with Socrates: On the Nicomachean Ethics (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press).

BENARDETE, Seth (4 April 1930—2001 November 14).

2000. The Argument of Action: Essays on Greek Poetry and Philosophy (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press).

BRONSTEIN, David.

2012. “The Origin and Aim of Posterior Analytics II.19” in Phronesis 57: 29-62.

2016. Aristotle on Knowledge and Learning: The Posterior Analytics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

CHARLES, David.

2010. “The Paradox in the Meno and Aristotle’s Attempts to Resolve It” in Definition in Greek Philosophy (ed. David Charles) (Oxford: Oxford University Press: 115-150).

COOPER, John M. (29 November 1939—2022 August 8).

1997. Plato: Complete Works (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company).

FOWLER, H.N.

1960. Plato (ed T.E. Page). Loeb Classical Library, vol. I (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

GOTTHELF, Allan (30 December 1942—2013 August 30).

1987. “Aristotle’s conception of final causality” in Philosophical issues in Aristotle’s Biology (ed. Allan Gotthelf and James G. Lennox) (New York: Cambridge University Press: 204-42).

GILL, Mary Louise (31 July 1950—).

2010. “Division and Definition in Plato’s Sophist and Statesman” in Definition in Greek Philosophy (ed. David Charles) (Oxford: Oxford University Press: 172-202).

HAMLYN, D.W. (1 October 1924—2012 July 15).

1976. “Aristotelian Epagoge” in Phronesis 21: 167-84.

HERODOTUS (c.484—425bc).

1958. Histories 1.8.6 (ed. Legrand). Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

HINTIKKA, Jaakko (12 January 1929—2015 August 12).

1980. “Aristotelian Induction” in Revue Internationale de Philosophie 34: 422-39.

HIPPOCRATES (460—370bc).

c.450-00bc. De prisca medicina (15.3-8) in Hippocrates et Corpus Hippocraticum Med., Oeuvres complètes d’Hippocrate 1. É.Paris: Baillière.

HOUSER, R.E.

2011. “The Language of Being and the Nature of God in the Aristotelian Tradition” in Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association 84: 113-32.

KLEIN, Jacob (3 March 1899—1978 July 16).

1965. A Commentary on Plato’s Meno (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press).

KNUUTTILA, Simo (8 May 1946—2022 June 17).

1993. “Remarks on Induction in Aristotle’s Dialectic and Rhetoric” in Revue Internationale de Philosophie 47: 78-88.

LAMB, W.R.M. (5 January 1882—1961 March 27).

1977. Plato. Loeb Classical Library, vol. I (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

LENNOX, James G. (11 January 1948—).

1987. “Divide and Explain: the Posterior Analytics in Practice” in Philosophical Issues in Aristotle’s Biology (ed. Allan Gotthelf and James G. Lennox) (New York: Cambridge University Press: 70-89).

2001. Aristotle on the Parts of Animals: I-IV (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

2010. “Bios and Explanatory Unity in Aristotle’s Biology” in Definition in Greek Philosophy (ed. David Charles) (Oxford: Oxford University Press: 329-55).

2011. “Aristotle on the Norms of Inquiry” in HOPOS: The Journal of the International Society for the History of Philosophy 1, 1.

MCGINNIS, Jon.

2003. “Scientific Methodologies in Medieval Islam” in the Journal of the History of Philosophy 41, 3: 307-27.

MCKIRAHAN, Richard, Jr.

1983. “Aristotelian Epagoge in Prior Analytics 2.21 and Posterior Analytics I.I” in the Journal of the History of Philosophy 21: 1-13.

OWENS, Joseph, C.S.B. (17 April 1908—2005 October 30).

1951. The Doctrine of Being in the Aristotelian Metaphysics (Toronto, Canada: PIMS).

1955. “Our Knowledge of Nature” in Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association, 63-86.

1959. The History of Ancient Western Philosophy (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc.).

PELLEGRIN, Pierre.

1986. Aristotle’s Classification of Animals: Biology and the Conceptual Unity of the Aristotelian Corpus (tr. Anthony Preus) (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press).

PIEPER, Josef (4 May 1904—1997 November 6).

1964. Enthusiasm and Divine Madness: On the Platonic Dialogue Phaedrus (tr. Richard and Clara Winston) (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World).

PETERS, F.E. (23 June 1927—2020 April 30).

1967. Greek Philosophical Terms: A Historical Lexicon (New York: New York University Press).

PLATO (c.429/424—348/347bc).

c.399–95bc. The Dialogues of Plato, Volume 1: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Gorgias, Menexenus, English translation by R.E. Allen (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984).

c.399-90bc. Laches.

c.388–67bc. Parmenides.

c.388–67bc. Πολιτεία, translated into Latin as Res Publica and thus transmitted to English as “The Republic”, in the English translation by Allan Bloom, The Republic of Plato (New York: Basic Books, 1991).

c.365–61bc. Sophist, in the English translation by Seth Benardete (The University of Chicago Press, 1984).

c.360–48bc. Philebus.

REEVE, C.D.C. (10 September 1948—).

2012. Action, Contemplation, and Happiness: An Essay on Aristotle (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

ROBINSON, Richard.

1953. Plato’s Earlier Dialectic (London, UK: Oxford University Press).

SALLIS, John.

1996. Being and Logos: Reading the Platonic Dialogues (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press).

TAYLOR, A.E. (22 December 1869—1945 October 31).

1911. “The words εἶδος, ἰδέα in Pre-Platonic Literature” in Varia Socratica (Oxford, St. Andrews University Publications, IX).

THOMAS AQUINAS (1225—1274).

c.1252/56. De principiis naturae.

TKACZ, Michael W.

2007. “Albert the Great and the Revival of Aristotle’s Zoological Research Program” in Vivarium 45 (Brill): 30-68.

2017. “Albertus Magnus, Averroes and the Recovery of the Aristotelian Zoological Research Program” in Albert the Great and the Arabic Peripatetics: Translation, Appropriation, Transformation (ed. Richard Taylor and Katja Krause) (Leiden: E. J. Brill).

UPTON, Thomas.

1981. “A Note on Aristotelian Epagoge” in Phronesis 226: 172-76.

WAGNER, Daniel C. and BOYER, John.

2019. “Albertus Magnus and St. Thomas on What is “Better-Known” in Natural Science” in Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association, 93: 199-225.

WAGNER, Daniel C. and SAVINO, Sr. Damien Marie, FSE

2022. “Disputatio on the Distinction between the Human Person and Other Animals: The Human Person as Gardener,” in Studia Gilsoniana, 11, no. 3 (July–September 2022): 471–530.

WAGNER, Daniel C.

2018. φύσις καὶ τὸ ἀνθρώπινον ἀγαθόν: The Aristotelian Foundations of the Human Good, PhD dissertation (available via ProQuest).

2020. “The Logical Terms of Sense Realism: A Thomistic-Aristotelian & Phenomenological Defense” in Reality: a journal for philosophical discourse, 1.1: 19-67.

2021. “On Karol Wojtyła’s Aristotelian Method: Part I: Aristotelian Induction (ἐπαγωγή) and Division (διαίρεσις)” in Philosophy and Canon Law, Vol. 7/1: Semicentennial of Karol Wojtyła’s “Person and Act”: Ideas—Contexts—Inspirations (I).

WALLACE, William A. (11 May 1918—2015 March 2).

1996. The Modeling of Nature: Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Nature in Synthesis (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press).

WILLIAMSON, Robert B.

1976. “Eidos and Agathon in Plato’s Republic” in Essays in Honor of Jacob Klein (Annapolis, MD: St. John’s Press).

[1] Portions of this study treating Aristotle’s logical method of division in APo and in its application in the life sciences (focusing on De Anima and De Partibus Animalium) are taken from my more more comprehensive and extended textual approach in Wagner 2021, “On Karol Wojtyła’s Aristotelian Method: Part I: Aristotelian Induction (ἐπαγωγή) and Division (διαίρεσις)” in Philosophy and Canon Law, which also parallels Wagner 2018, φύσις καὶ τὸ ἀνθρώπινον ἀγαθόν: The Aristotelian Foundations of the Human Good, PhD dissertation (available via ProQuest). Significant portions of this study treating Plato on division are also taken from chapter 1 of the latter work.

[2] c.348-47bc: APo I.2 71b20-23 (emphasis added): εἰ τοίνυν ἐστὶ τὸ ἐπίστασθαι οἷον ἔθεμεν, ἀνάγκη καὶ τὴν ἀποδεικτικὴν ἐπιστήμην ἐξ ἀληθῶν τ’ εἶναι καὶ πρώτων καὶ ἀμέσων καὶ γνωριμωτέρων καὶ προτέρων καὶ αἰτίων τοῦ συμπεράσματος· οὕτω γὰρ ἔσονται καὶ αἱ ἀρχαὶ οἰκεῖαι τοῦ δεικνυμένου. Or, “Accordingly, if scientific knowledge (τὸ ἐπίστασθαι) is as we have stated, it isnecessary (ἀνάγκη) that demonstrative science (τὴν ἀποδεικτικὴν ἐπιστήμην) be from principles that are true, primary, un-middled, better known, prior to and also causative of the conclusion; for in this manner the principles (αἱ ἀρχαὶ) will be the proper belongings [i.e., essential attributes] of what is shown.” The translations of Aristotle are my own. As will become apparent respect to APo, I have had reference to and been in dialogue with the translations of Apostle (1981), Mure (1928), Tredennick (1960), and Barnes (1993).

[3] Greg Bayer and David Bronstein both reject this interpretation that APo II.19 sets out induction as the method by which the first principles of a science are obtained. See Bayer 1997: “Coming to Know Principles in Posterior Analytics II 19” in Apeiron 30: 109-42 (“Coming to Know Principles” hereinafter); Bronstein 2012: “The Origin and Aim of Posterior Analytics II.19” in Phronesis 57: 29-62 (“The Origin and Aim of APo” hereinafter); Bronstein 2016: Aristotle on Knowledge and Learning: The Posterior Analytics (Aristotle on Knowledge and Learning hereinafter). See below, n.7, for my response.

[4] For Plato on ἀνάμνησις, see c.385bc: Phaedo 72e-77a and c.399–95bc: Meno 81a-d.

[5] Greg Bayer, for example, uses the description. 1997: “Coming to Know Principles”, 110.

[6] Generally, the text APo II.19 is taken as Aristotle’s treatment of induction (ἐπαγωγή), which he has also explicitly set down as the method for obtaining knowledge of the first principles of a science in APo I.1, 3, and 18. Jon McGinnis has helpfully divided scholarly interpretations of the text into two schools. 2003: “Scientific Methodologies in Medieval Islam” in the Journal of the History of Philosophy 41, 3: 307-27, esp. 316, n.14-16. The first school, focusing on Prior Analytics II.23, takes induction as a type of proof or justification for establishing the principles of a science that comes through the many particulars; cf. Hamlyn 1976: “Aristotelian Epagoge” in Phronesis 21: 167-84; McKirahan 1983: “Aristotelian Epagoge in Prior Analytics 2.21 and Posterior Analytics I.I” in the Journal of the History of Philosophy 21: 1-13 (esp. 11-12). A second school of thought, reading APo II.19 primarily through the genetic account at c.348-30bc: Metaphysics I.1, takes induction as an account of the psychological generation of scientific concepts; cf. Upton 1981: “A Note on Aristotelian Epagoge” in Phronesis 226: 172-76; Hintikka 1980: “Aristotelian Induction” in Revue Internationale de Philosophie 34: 422-39; Knuuttila 1993: “Remarks on Induction in Aristotle’s Dialectic and Rhetoric” in Revue Internationale de Philosophie 47: 78-88. There is no need to see these schools as incommensurate and, as McGinnis points out, Bayer goes some way toward synthesizing the insights of these two schools of thought and avoiding the shortcomings of both. See 1997: “Coming to Know Principles”, 109-42. David Bronstein rejects the standard reading that APo II.19 treats the method for how the first principles of a science come to be known, limiting its scope to a treatment of the ultimate ἀρχή or source of knowledge in sense-perception. See 2012: “The Origin and Aim of APo”, 29-62; 2016: Aristotle on Knowledge and Learning. Bayer also rejects the claim that Aristotle holds that induction is the method by which the first principles of a science are apprehended. See 1997: “Coming to Know Principles”, 109-42. I have argued elsewhere that this interpretation is not supported by the text, though I agree with Bronstein that the method by which first principles or definitions of a science are obtained is division, in accord with APo II.1-10 and, esp. 13-14. I read division, however, as a form of induction, which has multiple senses. Cf. Wagner 2018: φύσις καὶ τὸ ἀνθρώπινον ἀγαθόν: The Aristotelian Foundations of the Human Good), 118-43.

[7] 1993: Posterior Analytics, English translation by Barnes, 262.

[8] Hamlyn (1976: “Aristotelian Epagoge” in Phronesis 21: 177) holds this, since the text does not explain how some animals get sense-perceptive universals by which to form judgments.

[9] Bayer 1997: “Coming to Know Principles”, 109.

[10] Bronstein 2016: Aristotle on Knowledge and Learning, 3.

[11] Bronstein 2012: “The Origin and Aim of APo”, 42. Bronstein’s position is nuanced, as he rightly holds that the method for moving from the sense-perceptive universal to knowledge of first principles has already been treated in APo II.1-10 and 13, where Aristotle sets out his doctrine of division. Yet, understanding Aristotle’s use of division in this text itself, I hold, will show that that the charge of there being a “gap” in the presentation is inaccurate.

[12] For a helpful treatment of the value and limitations of dichotomous division in the Sophist and Statesman, see Gill 2010, “Division and Definition in Plato’s Sophist and Statesman” in Definition in Greek Philosophy, 172-202.

[13] c.348-47bc: APo II.13-14, and c.331bc: De partibus animalium I.2.

[14] For excellent treatments of Aristotle’s critique of dichotomous division, see Balme 1987: “Aristotle’s use of division and differentia” in Philosophical Issues and Aristotle’s Biology, 74-78; Tkacz 2007, “Albert the Great and the Revival of Aristotle’s Zoological Research Program” in Vivarium 45: 30-68; Tkacz 2017, “Albertus Magnus, Averroes and the Recovery of the Aristotelian Zoological Research Program” in Albert the Great and the Arabic Peripatetics: Translation, Appropriation, Transformation. On Aristotle’s method of definition/division and explanation in the life sciences, see also Pellegrin 1986, Aristotle’s Classification of Animals: Biology and the Conceptual Unity of the Aristotelian Corpus, 48-49; Gotthelf 1987, “Aristotle’s conception of final causality” in Philosophical issues in Aristotle’s Biology, 204-42.; Lennox 1987, “Divide and Explain: the Posterior Analytics in Practice” in Philosophical Issues in Aristotle’s Biology, 70-89; Lennox 2010, “Bios and Explanatory Unity in Aristotle’s Biology” in Definition in Greek Philosophy, 329-55.

[15] See Wallace 1996, The Modeling of Nature: Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Nature in Synthesis, esp. 157-89. Wallace uses the phrase “powers model” to explain human nature. Perfection is obtained through the formation of a proper habit and action of the various human faculties. The propriety of the habit is determined through an analysis of the faculty (power) in relation to the object to which it is ordered by nature, which is why the phrase “power-object” model used here is appropriate. In commenting on the human good and the human ἔργονin Nicomachean Ethics (1097b22-23), Ronna Burger refers to Aristotle’s appeal to the acts of the carpenter and the shoe maker along with those of the organs (the hand, eye, foot, etc.), as a “model” that is “twofold”, although she does not explain the model along the lines of power and object, but rather in terms of parts in relation to wholes. See 2008: Aristotle’s Dialogue with Socrates: On the Nicomachean Ethics, 31. For my treatment of this model of division for the sake of distinguishing human intelligence and technological production from animal cognition and production, see Sr. Damien Marie Savino, FSE and Daniel Wagner 2022: “Disputatio on the Distinction between the Human Person and Other Animals: The Human Person as Gardener,” in Studia Gilsoniana, 11.3 (July–September 2022): 471–530.

[16] c.399–95bc: Euthyphro, 5c9 (emphasis added): “…ποῖόν τι τὸ εὐσεβὲς φῂς εἶναι καὶ τὸ ἀσεβὲς…” The translations of Plato are my own. I have had reference to or consulted with the translations of Grube (1997), Allen (1984), Lamb (1977), Fowler (1960), and Bloom (1991). For a parallel approach to definition in another early Platonic dialogue, see also c.399-90bc: Laches, esp. 190d-192b, where a definition of courage is sought through the identification of the common quality of all things courageous.

[17] c.399–95bc: Euthyphro, 5d1-4: “ἢ οὐ ταὐτόν ἐστιν ἐν πάσῃ πράξει τὸ ὅσιον αὐτὸ αὑτῷ, καὶ τὸ ἀνόσιον αὖ τοῦ μὲν ὁσίου παντὸς ἐναντίον, αὐτὸ δὲ αὑτῷ ὅμοιον καὶ ἔχον μίαν τινὰ ἰδέαν…” Or, “Is not the pious itself the same with respect to itself in every act, and, on other hand, [is not] the impious opposite of all that is pious, and itself the same with respect to itself, also possessing some single form (ἰδέαν).” On the translation of ἰδέαν as “form”, see pp. 8-9, and n.23-24, below.

[18] Ibid, 6d10-11 (emphasis added): “…ἀλλ’ ἐκεῖνο αὐτὸ τὸ εἶδος ᾧ πάντα τὰ ὅσια ὅσιά ἐστιν.”

[19] The doctrine of separate (χωρὶς) forms (εἰδή) rejected by Aristotle is most clearly stated at c.388–67bc: Parmenides 130b-d and 133c and c.360–48/7bc: Philebus 15b.

[20] The rejection of the doctrine of separate ideas is clear already at Categories 5 (3b10-18), where Aristotle shows that the universals, genus, species, and difference, cannot be separately existing individuals as they are predicated of many. Aristotle is said, of course, to have formulated the famous “third man” argument against the theory of separate ideas, as expressed in Parmenides (132a-b), and he himself accepts it as is clear from c.348-30bc: Metaphysics (990b17; 1039a2; 1079a13), and c.340bc: Sophistical Refutations (178b36).

[21] ἰδέα is taken from the infinitive form, ἰδεῖν. Commentators have long pointed out that Plato uses the terms synonymously. See, e.g., Taylor 1911: “The words εἶδος, ἰδέα in Pre-Platonic Literature” in Varia Socratica, 189-90; Owens 1959: The History of Ancient Western Philosophy, 198; Sallis 1996: Being and Logos: Reading the Platonic Dialogues, 383.

[22] In commenting on c.388–67bc: Republic 475e-476d, Sallis notes that the term ἰδέα, from the infinitive form, ἰδεῖν, “refers more pointedly to the look of something, to its way of showing itself to a seeing.” 1996: Being and Logos: Reading the Platonic Dialogues, 383. He then emphasizes that the terms should not be “thoughtlessly translated as ‘form’ or ‘idea.’” Ibid. His point is that the terms should not be reductively treated as meaning something like ‘concept’, or ‘separated-Form’, or the fact that they entail something really in the ‘seen’ will be lost on us as readers. See ibid. As will be seen presently, however, since the term has already come to signify universality as a classificatory concept prior to Plato, the literal translation, ‘look’, is not acceptable.

[23] See Taylor’s most impressive study, 1911: “The words εἶδος, ἰδέα in Pre-Platonic Literature”. Taylor’s main argument is to show that the terms are used by Socrates already to mean more than simply the literal ‘look’ of things. He makes this case by appealing to pre-platonic literature. He looks at non-philosophical/technical, Pythagorean, rhetorical, and medical writings, arguing that ultimately, it is the mathematical sense of εἶδος, which bleeds into rhetoric and medicine, that Plato attributes to Socrates and adopts and develops himself. Ibid, 180. εἶδος was hardly used in common language; it is absent from Xenophon, and rarely appears in Herodotus, Thucydides, or Aristophanes. When it is found in these authors, it means figure or physique. There is a fine example of the term employed in the predication of physical beauty, Herodotus, Histories (1958), where a husband is spoken of as “…praising immeasurably the figure (τὸ εἶδος) of his wife.” Taylor points out, then, that in its common usage it did not imply a distinction between appearance and how something “really” is. This, he argues, came from Ionian Science, particularly mathematics, rhetoric, and medicine. Taylor 1911: “The words εἶδος, ἰδέα in Pre-Platonic Literature”, 181-82.

[24] Taylor shows that the ultimate source of the modification of the terms is Pythagorean mathematics and its influence on Pre-Socratic Philosophical thought. 1911: “The words εἶδος, ἰδέα in Pre-Platonic Literature”, 246-47.

[25] Ibid, 211-12.

[26] See Plutarch c.100ad: Adversus Colotem, in Plutarchi moralia (1110.F.5-1111.A.1-4), vol. 6.2, ed. Westman, R. (post M. Pohlenz) (Leipzig: Teubner, 1959, 2nd ed.); Taylor 1911: “The words εἶδος, ἰδέα in Pre-Platonic Literature”, 247. One of the primary qualitative features Democritus attributes to the atoms is σκῆμα (‘shape’) which was also taken up by Isocrates as synonymous with εἶδος.

[27] For the explicit connection of the atomist tradition to the medical, see Hippocrates c.450-00bc: De prisca medicina, 15.3-8, (1973). Cf. Taylor 1911: “The words εἶδος, ἰδέα in Pre-Platonic Literature”, 214-16. In this text, the terms have added to their meanings of ‘formal structure’ or ‘order’ the distinct notion of a common ‘sort’, ‘type’, or ‘class’. Here, various contraries are referred to—hot and cold and dry and moist—and it is noted that they are never actually discovered existing in themselves as “not in community with a single other form” (μηδενὶ ἄλλῳ εἴδεϊ κοινωνέον). The point is that, in practice these features are found in compounds with other features: hot with astringent, or damp, etc. The author is contrasting this fact with the Empedoclean approach to the elements existing as simples in themselves, and suggesting that the τέχνη of medicine should have nothing to do with such a theory, since no such simples are discovered, and since proper prescription to a patient will require expression of the treatment not merely as a single form, but as the compound of two or more forms. Thus, two senses of εἶδος are discerned in the text: the Empedoclean sense of εἶδος as applied to simple bodies and the author’s own treatment of εἶδος, rather, as a simple sensed-quality. What is key is that εἶδος is being used to signify types in both cases: types of simple bodies or sensed qualities. Simple bodies or sensed qualities are united under a single heading: εἶδος.

[28] As treated by Taylor 1911: “The words εἶδος, ἰδέα in Pre-Platonic Literature”, 220-21, the work of the Hippocratic corpus is Ἐπιδημίων ά.: “…most of the women who died were of this [bodily] constitution (εἴδεος).” Taylor sees this as the decisive passage in the medical profession where εἶδος comes to explicitly signify a “sort” or “class”. Ibid. Compare this passage to Aristotle’s distinction between knowledge of the fact and knowledge of the cause of the fact at c.348-30bc: Metaphysics I.1, 981a5-12.

[29] c.399–95bc: Euthyphro, 6e4-5.

[30] Οὐσία is an abstractive noun formed from the feminine present participle of εἰμί. Its core etymological meaning is ‘that which is one’s own’, or ‘one’s property’. It is clear that this is precisely what Socrates is looking for in this context regarding the pious. For an extremely helpful treatment of the term οὐσία and the history of its various translations in Latin and English, see Owens 1951: The History of Ancient Western Philosophy,139, and Houser 2011: “The Language of Being and the Nature of God in the Aristotelian Tradition” in Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association 84: 117. These accounts will be returned to below, in the treatment of Aristotle on οὐσία.

[31] In his 1965: Commentary on the Meno, Jacob Klein translates οὐσία as “beingness” or “being”, and he notes that it has the “flavor of a technical term” for Plato, meaning that it will signify aspects of things usually not discussed in common speech. See 1965, 47-48. This literal translation, rather than ‘essence’ or ‘nature’, which are used to indicate that Plato is after the formal or quidditative meaning of the term, is preferred here as it helps us to avoid imposing the Platonic doctrine of Ideas on the dialogue and the approach to definition. For οὐσία as ‘essence’, see Fowler’s translation in 1960: Plato, 41; for οὐσία as ‘nature’, see the translation of Grube in Cooper 1997: Plato: Complete Works, 11.

[32] Socrates uses the precise formulation at c.399–95bc: Euthyphro, 11b4-5: “ἀλλ’ εἰπὲ προθύμως τί ἐστιν τό τε ὅσιον καὶ τὸ ἀνόσιον;” Or, “But tell me with good will, what is (τί ἐστιν) the holy and the what is the un-holy?”

[33] c.399–95bc: Euthyphro, 12e5-7: “τὸ μέρος τοῦ δικαίου εἶναι εὐσεβές τε καὶ ὅσιον, τὸ περὶ τὴν τῶν θεῶν θεραπείαν…” It is, perhaps, hasty to attribute a full-fledged distinction between genus, species, and difference to Plato here, such as we will later see expressed in Aristotle’s Categories. Cf. Balme 1987, “Aristotle’s use of division and differentia” in Philosophical Issues and Aristotle’s Biology, 69-89. It is at least clear, however, that Plato grasps and employs a distinction between broader and more specific classification and that knowing what something is entails grasping it both as part of a larger whole and as different from other beings belonging to the same whole. Here, the larger whole is justice, and the point of differentiation is found in that this justice pertains to a relation to the gods, and not other humans. Allen certainly sees the distinction between genus, species, and difference present here, at c.399–95bc: Euthyphro (1984), 39.

[34] c.399–95bc: Meno, 70a.

[35] c.399–95bc: Meno, 71b3-4: “ὃ δὲ μὴ οἶδα τί ἐστιν, πῶς ἂν ὁποῖόν γέ τι εἰδείην;” Or, “If I do not know what it is (τί ἐστιν), how could I know any quality [of it]”. See, again, Meno, 75d5: “…τί φῂς ἀρετὴν εἶναι;” Or, “what do you say that virtue is?” On the need to know the definition before knowing an attached quality, cf. Sallis 1996: Being and Logos: Reading the Platonic Dialogues, 65-66.

[36] c.399–95bc: Meno, 72b2-3.

[37] c.399–95bc: Meno, 72c6-8: “κἂν εἰ πολλαὶ καὶ παντοδαπαί εἰσιν, ἕν γέ τι εἶδος ταὐτὸν ἅπασαι ἔχουσιν δι’ ὃ εἰσὶν ἀρεταί.” Or, “Even if the many [virtues] are varied in some manner, yet they all surely possess some one identical form (εἶδος), on account of which they are virtues.”

[38] c.399–95bc: Meno, 73e.

[39] c.399–95bc: Meno, 75b8-11. “Φέρε δή, πειρώμεθά σοι εἰπεῖν τί ἐστιν σχῆμα. σκόπει οὖν εἰ τόδε ἀποδέχῃ αὐτὸ εἶναι· ἔστω γὰρ δὴ ἡμῖν τοῦτο σχῆμα, ὃ μόνον τῶν ὄντων τυγχάνει χρώματι ἀεὶ ἑπόμενον.” Or, “Come, let me attempt to state the definition (τί ἐστιν) of figure for you. Look as to whether you accept it to be this: let figure be this for us, that alone of beings which happens always to be belonging to/with color.” It is clear that Socrates thinks this definition is adequate and that he wants Meno to use it as a model for defining virtue, as he says immediately after giving it: “I would be pleased if you could tell me, even in this manner, what virtue is.” See, Meno, 75b11-75c1: “ἐγὼ γὰρ κἂν οὕτως ἀγαπῴην εἴ μοι ἀρετὴν εἴποις.” The “even in this manner” in this statement suggests, however, that there would be something missing about the definition as a model in the case of virtue. While this example does show the necessity figure belonging to color, it does not itself fit with the Socratic criteria that a definition locate a species or part within a larger genus or whole. Figure is not a species of color. Presumably, then, Socrates is looking for an account of virtue which displays it as necessarily ‘belonging’ to something in this manner, but ideally the ‘something’ would be some kind or genus.”